The Hotel Workout

/By James Walker, CCS, STM, Biosig, Master Trainer

I call this the Hotel workout but it can be done anywhere, in little time, no excuses…the hotel didn’t have a gym, the gym was too crowded, I didn’t know how to use the equipment, etc, etc…Remember at the end of the day, week, month, and year, something is better than nothing! So ‘Just Do It’!

Perform this workout in a circuit fashion, going from the first exercise to the second and to the third, i.e., A1, A2, A3, doing three rounds for 10 reps or 3 x 10. This will helps create the volume and the physiological response, i.e., metabolic elevation, growth hormone production, muscle growth, and fat loss that’s desired.

Time permitting you could do up to 5 circuits or rounds. This program is do-able, convenient, and accessible for you, anywhere or time, no excuses! This can be done on a Monday/Wednesday or Tuesday/Thursday or Monday/Wednesday/Friday or Tuesday/Thursday/Saturday schedule.

Below is a brief description of a Two or Three Day Workout Format:

Day 1 – 10 reps each for 3 sets/rounds.

A1. standing bodyweight squat; – with feet hip width apart or slightly wider and hands on waist, lower body down towards floor as far as possible on a 3-4 tempo and return on a 2 tempo. 10 reps.

A2. incline pull up with towel or rope; - with a knot on the end (requires a secure door or rail or banister; or wedge middle of a folded towel between door and door frame, shut, secure, or lock the door so it doesn’t open and will safely support your body weight; or wrap a towel around a rail or banister that’s strong and sturdy enough to support your weight; hold the ends of the towel in each hand and position feet on floor close to the bottom of door or rail, lean body away from the door as far as possible, support your weight with the towel and your arms, pull body up to hands or towel on a 2 tempo and return on a 3-4 tempo. 10 reps.

A3. Lying hip lifts; – lay on the floor with your hands by sides and your feet up towards the ceiling, lift your hipsoff the floor 2-3 inches or as high as possible on a 1 tempo and return on a 2 tempo. 10-20 reps.

Day 2 – 10 reps each for 3 rounds.

A1. standing split squat; – in a lunge stance with one foot forward and the other foot back, on forefoot with heel raised, lower torso down towards floor as far as possible on a 3-4 tempo and return on a 2 tempo. 10 reps.

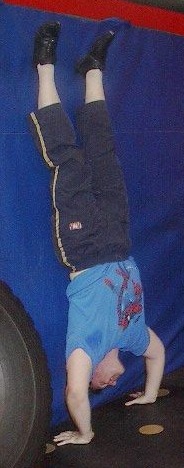

A2. push up against a wall or on the floor; – with hands against the wall, feet hip width apart approximately 3-5 feet from the wall, lean towards the wall, lower torso towards the wall on a 3-4 tempo and return on a 2 tempo; or in a push up position with hands and feet or knees on floor, lower torso towards the floor on a 3-4 tempo and return on a 2 tempo. 10 reps.

A3. Crunch; - laying on the floor with both legs bent and hands by sides on floor, slide your hands down towards your hips and raise your torso up off the floor 2-3 inches on a 1 tempo and return on a 1 tempo. 10-20 reps.

Day 3 – 10 reps for 3 rounds.

A1. standing good-mornings; – with a hands by ears and elbow out to the sides and feet hip width apart, keep chest up and shoulders back, push hips back as far as possible and bend torso forward towards the floor (bow position) on a 3-4 tempo and return on a 2 tempo. 10-20 reps.

A.2. seated dip between chairs; – position your body in a seated or semi-squat position between two chairs of equal size with body supported by each hand on a chair seat or with your back and hips over the edge of the bed with hands by sides on bed for support, the legs and feet are out in front on the floor, lower the hips & torso down towards the floor as far as possible on a 3-4 tempo and return on a 2 tempo. 10 reps.

A3. Side hip lifts; - lay on one side supported by elbow and forearm against the floor with your feet slightly straddled (one forward & one back), raise your hips up off the floor as high as possible on a 1 tempo and return on a 2 tempo. 10 reps each side.

Remember take your time and don’t sweat it. Even if this is easy or only takes 10 minutes at the end of the week, month, and year you will have done much more work and burned many more calories as opposed to doing zero! Each round should take 2 -3 minutes, followed by a 1-2 minute rest period. The entire workout should take between 10-20 minutes depending on the length of your rest periods.

‘Train Safe, Smart, & Results Driven’