By James Walker CCS, STM, BioSig, Master Trainer

In Part One we defined in-season training and listed the first two objectives when designing a program including exercise selection and energy system needs of the athlete. In Part Two we are discussing the remaining components that determine an athletes program, including rep range, weight load-intensity, muscle fiber type, and work volume consideration.

An intertwined objective to consider when determining the athlete’s program is choosing the correct rep range, weight load-intensity, and muscle fiber type that’s needed to improve their performance. A blocker or outside hitter in volleyball will need to develop and recruit their fast twitch fibers, so doing between 1-6 reps, with 95-80% of their one rep max (1RM), for their phasic muscles will accomplish this. Similarly, a running back in football will benefit from the same intensity and rep ranges. Now these values can vary depending on the age, maturity, health, and genetic make up of the athlete but explosive power is the important component.

On the other hand the cross-country runner may require 15-20 reps or more, at 60-70% of their 1RM to improve their muscle endurance but may benefit from the 1-10 rep range at 75-95% 1RM to help with 100-400 meter surges or sprint finishes. Several of the top Olympic middle distance runners employ this method in their training.

Either of these athletes may require a different rep range and intensity level to address their individual structural needs. In general if their tonic or postural muscles need work a rep range of 8-15, at an intensity of 80-70% of 1RM, may be required. The specific needs of the individual will always be the most beneficial to them.

The last proponent to consider is the appropriate volume of work needed to maintain and/or improve ability without over-training. The primary focus during the season should be the development of the necessary skills, ability, and strategy needed to perform the sport or position at the highest level. The secondary focus should be on maintaining and/or improving power, strength, and conditioning that was developed during the off-season. Usually most in-season practice is devoted to game preparation, sports skills, drills, strategy, tactics, plays, and related task. Therefore most of the repetition and conditioning will come from those activities, so strength related training only needs to occupy about 10-15% of the athletes total weekly time. That can be accomplished in one or two sessions, with consideration given to adequate recovery time before the day of the competition. Ideally the strength training should enhance practices, skills, abilities, and performance, while reducing the injury potential.

Likewise, practices shouldn’t injure the athlete or hinder their strength training but allow for mutual improvement, or a complete synergistic relationship. A big mistake often made is to abandon strength training during the season. This will usually start to gradually impact performance or increase injury potential after about 14 days. The athlete may start the season strong, fast, powerful, explosive, and energetic but within a few weeks will start to exhibit weakness, slowness, sluggishness, or tiredness.

Coincidently, the residual effects from strength training may last up to 10 days; so training a muscle group at least once a week or every 7 days will allow maximal recovery and strength gains. Often world-class sprinters require up to 7-10 days to fully recover, after running a personal record.

So a cheerleader who practices about 10 hours a week, excluding a 3-hour Friday evening game, at 10% of her weekly practice time the strength training would require about 1 hour to complete. Depending on equipment, facility, scheduling, etc, the 1-hour time could be divided into two 30-minute segments as to minimize time away from skills practice. This could be accomplished with a 30-minute strength training session on Saturday (the day after the game), followed by another 30-minute session on Monday or Tuesday, which would also give plenty of recovery time prior to the game. Each session would be comprised of 4 strength-power exercises for 4-8 reps, times 2 sets; and 2-4 structural exercises for 8-15+ reps, for 1-2 sets. The exercise selection could be different for each session to target various or specific muscle groups as well.

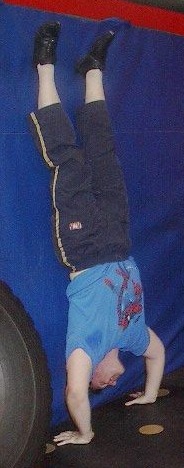

As you can see the exercise selection, energy system, rep range, weight load-intensity, muscle fiber type, and volume all comply with her in-season strength training needs. The exercise selection should depend on her individual needs and ability level. Likewise, considering the amount of impact and repetitive stress related injuries that cheerleaders accrue i.e., sprains, strains, twists, pulls, fractures, and soft-tissue adhesions, this would help to address those concerns. Not to mention the additional strength to help with the skills execution.

In conclusion, the benefits of the in-season strength training far out-way the time, cost, injury potential, and other factors involved. The correct, safe, and scientific approach should consider exercise selection, energy system, rep range, weight load-intensity, muscle fiber type, and volume to best address the athletes in-season needs.